NARRAGANSETT, March 18, 2016 – It all started with Mr. Southard.

NARRAGANSETT, March 18, 2016 – It all started with Mr. Southard.

Carrie McDonough was a high school student when Don Southard, her beloved chemistry teacher, told her about the origins of acid rain: sulfur dioxide emissions—usually from smokestacks—that react with water molecules to produce acids.

She was fascinated by the science, but also troubled by the consequences: a pernicious effect on the environment. “Since then, I’ve always wanted to learn more about how humans alter our environment,” she says, “and what that means for the future of the planet and human health.”

Her interest in environmental pollution is still thriving today at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography where the 29-year-old Cleveland native is researching chemicals contaminating the Great Lakes, the largest group of fresh water lakes in the world.

McDonough recently submitted a paper to Environmental Science and Technology about her studies of chemicals polluting Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Her research is important, she says, because it could prompt regulators and policymakers to pay more attention to what’s dumped in the water and also inspire consumers to make better decisions about the products they use and buy.

McDonough’s work in GSO’s Lohmann Lab centers on using environmental monitoring tools to measure chemicals used in consumer products and which only recently have been recognized as possibly toxic. Surprisingly, these chemicals are not strongly regulated.

She is studying two groups of compounds: synthetic fragrances, which are added to shampoo, soap, deodorant, detergent and cleaning supplies to give the products a pleasing smell; and flame retardants, which are added to furniture, textiles, plastic toys and electronics to decrease flammability.

It’s impossible to precisely identify fragrance chemicals in products, McDonough says, because the mixes are considered proprietary information, or a trade secret: The ingredients on bottles usually just say “fragrance.”

“Unless it says ‘natural fragrance’ we don’t really know which of the thousands of chemicals manufacturers are using in a product—and this is troubling,” says McDonough.

Synthetic fragrances get into waterways when people take showers or wash clothes. The chemical residue travels down the drain and ends up in wastewater treatment facilities, which remove some of the chemicals, but not all of them.

Flame retardants also pollute the environment. Because they’re very stable and don’t break down easily, these chemicals can slow combustion. But that stability means they can persist and bioaccumulate, or build up in marine life. They are often released into the air as molecules and adhere to airborne particles that are eventually deposited into the water.

These chemicals can be harmful to marine life as well as humans, says McDonough. Studies have shown that many of these pollutants can slow the growth of marine life, cause developmental abnormalities and interfere with reproduction. Humans are at risk, she says, because they eat the contaminated fish.

Growing up in the University Heights suburb of Cleveland, McDonough cultivated a love for science at an early age thanks to her mother, a neuroscientist, who took her to her laboratories and explained her research “in a simple and exciting way.”

Poetry and fiction writing propelled McDonough at Hathaway Brown School, as well as science, especially Southard’s chemistry class, where she learned that “I could apply science to real life.” Her next stop was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to study chemistry.

After graduating in 2008, she took a break from her studies for two years, playing rhythm guitar and singing in her Indie rock band “Fortran”—a shout-out to old computer language. From there, she went into environmental consulting for a firm in Massachusetts.

URI was her first choice for graduate school, mostly so she could work with Professor Rainer Lohmann, a leader in researching organic pollutants in the oceans, lakes and atmosphere.

For her dissertation, McDonough is returning to her roots, measuring those pollutants in Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, where she spent her summers as a child. To get her data, she uses polyethylene passive samplers—thin plastic sheets that absorb synthetic fragrances and flame retardants.

Since 2011, along with “citizen scientists” in the area, she has put about 300 sheets at various sites on the lakes. The sheets, which measure about 3 by 5 inches, absorb the chemicals in much the same way fatty tissues absorbs them. “They work in a sponge-like way. Chemicals accumulate inside the plastic over time,” says McDonough, who, along with a URI film student and media technologist, made a video that explains how to put out the sheets.

After two months or so in the water—and, in some cases, the air—the sheets were wrapped in protective foil and shipped to McDonough at GSO for analysis. First, she put the sheets in organic solvent to pull out the contaminants and then analyzed the solvent using a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer.

The sample was injected into a long, thin column inside an oven, where it was separated out. The sample then entered a detector that identified chemicals of interest. McDonough measured pollutants based on peaks that appeared on a computer screen.

In her recent paper she examined synthetic fragrances in the lakes in 2012. “We were able to detect these compounds in urban areas on the shore and near wastewater treatment plants,” says McDonough. “Generally, they seem to be at higher levels near densely populated areas, which suggests that these treatment plants are sources of those compounds.”

And that should trouble anyone concerned about protecting marine life—and human health. Think about it this way, she says: The chemicals get into mussels and snails, which is a food source for, say, fish. That fish is eaten by humans.

“Eating seafood is a major way people are exposed to toxic pollutants,” says McDonough. “It’s important for us to know what’s in the food we eat and the products we buy.”

Her next project is examining the data involving flame retardants in the Great Lakes. Eventually, she’d like to explore the toxicity of the pollutants for humans. Do they cause cancer? Do they harm reproduction? Growth?

“We’ve been exposed to thousands of chemicals since before we were even born,” she says. “Our generation needs to understand how these chemicals could affect our health before it’s too late.”

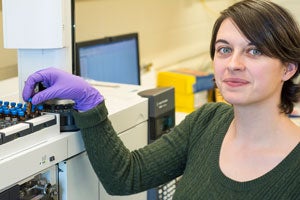

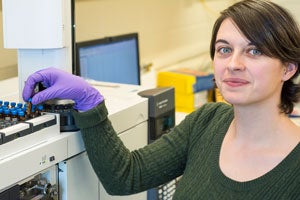

Pictured above: Carrie McDonough, 29, a doctoral student at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography who is studying chemical pollution in the Great Lakes. Her research is funded by The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, a program to improve water quality, clean up contaminated shorelines, protect and restore fish and wildlife habitat, combat invasive species and reduce storm water run off.

Photo by Nora Lewis.

GSO video: