KINGSTON, R.I., August 28, 2018 — Winning first prize at a national aviation competition has become a habit for the students of Bahram Nassersharif, distinguished University of Rhode Island professor of mechanical engineering.

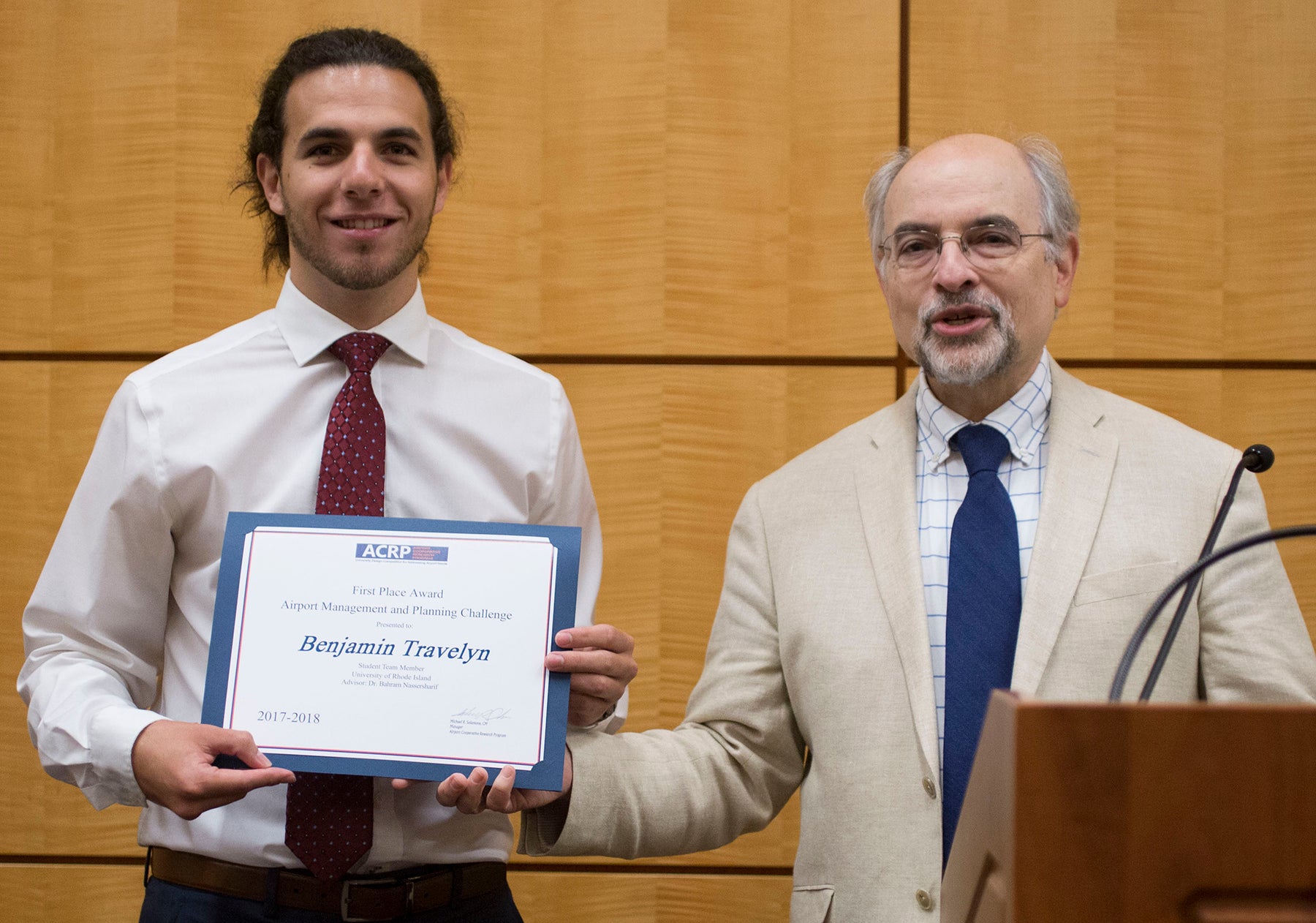

The Transportation Research Board’s Airport Cooperative Research Program selected teams of students from URI, the Florida Institute of Technology, and Purdue University for first-place prizes in different technical challenge areas. They were selected as part of the program’s University Design Competition for Addressing Airport Needs. First-place winners won $3,000.

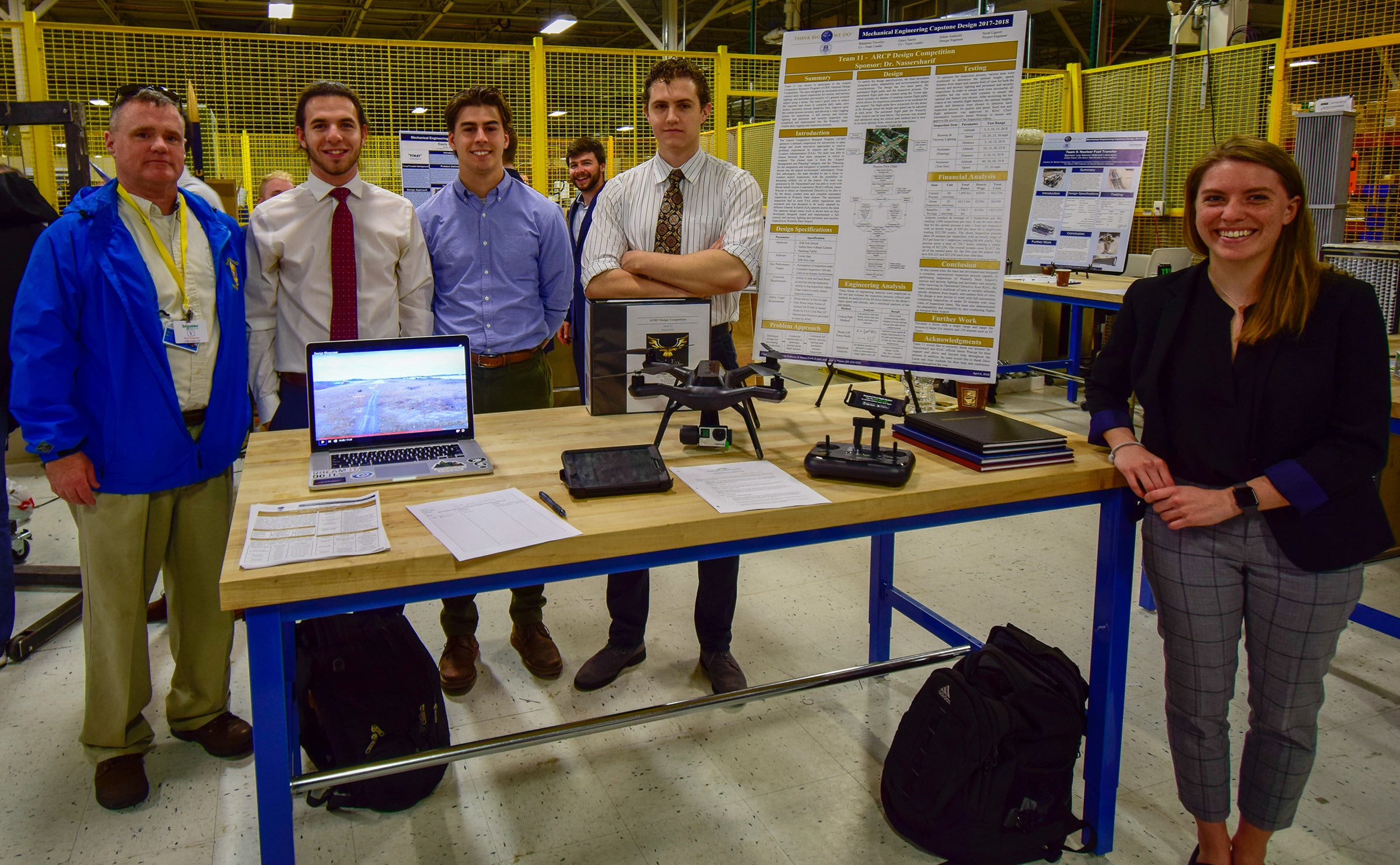

This year’s team of URI mechanical engineering students, Benjamin Travelyn, Grace Sanita, Scott Liguori and Julian Andriulli finished ahead of 10 other teams with its “Eagle Eye Project,” which investigated the effectiveness of using drones to conduct airport inspections. Travelyn, Sanita and Liguori earned their bachelor’s degrees in May. Andriulli, who has minors in music, math and Japanese, will earn his last three credits toward his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering when he completes a research project in Japan.

“We compete against some of the best schools in the country, including those with aviation programs, such as Purdue University, and graduate students from Florida International University,” Nassersharif said. “This makes me even more proud of what our undergraduate students are able to accomplish.

“One of the officials who reviews project proposals for the Transportation Research Board talked to me in Washington, D.C., right after one of our students presented on the project and said he was very interested in following up,” the professor said. “I am sure I will be talking with him about using drone technology for this purpose in the future.”

Travelyn, the student team leader, who now works at the Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Middletown, presented the results of the group’s work in Washington in late July.

“Teamwork was a big thing,” said the Cranston resident. “I operated the drone for the whole project, and I also learned about airport operations, the inspection process and protocols for us to be able to fly the drones in the airport.”

“I did a lot of work, but I wouldn’t have been able to do this without the help of everyone,” he said.

In 2016, another team of URI engineering students captured URI’s third first-place prize in the competition with its project, “Wingman 360,” a device that can protect planes from colliding while on the ground.

As in other years, “Eagle Eye” was the result of a year-long senior capstone project in Nassersharif’s class. Each year, the professor selects one or two projects to be entered in competitions.

This year, he selected Travelyn, Sanita, Liguori and Andriulli, and “Eagle Eye.”

The Airport Cooperative Research Program provides broad guidelines that address how to make airports better and safer using technology.

In the capstone class, the students spent the first semester researching and defining the problem, and conceiving solutions.

“I require every individual to generate 30 viable concepts, so for this team, there were 120 viable ideas,” Nassersharif said. “They sorted through each one, conducted engineering analyses and then selected a final idea.”

The students were allowed to test the drones at Newport and Westerly airports by James Warcup, chief aeronautics inspector with the Rhode Island Airport Corp.

The team also had to understand the inspection process and then replace a human inspector in a truck with a drone to examine such things as lighting, fencing and access.

Nassersharif said the inspections had to be completed in about 20 minutes because that’s about the life of a drone battery.

The students also had to program the drone to follow a specific flight path without the need for a human operator.

“They programmed the drone to fly to specific points at the airports,” Nassersharif said. “But initially, the students had to fly it manually to set altitude and orientation. Their goal was to demonstrate that the technology was transferable from one airport to another.

“At Westerly, the team discovered deer through the drone’s camera, which is something you couldn’t see from a truck at ground level. They also found turkey vultures eating a dead deer near the airport, which could pose a flight risk.”

As a result of their observations with the drone, the team attached noise generators to the drone to scare away the deer and turkey vultures.

Team member Grace Sanita, of Wrentham, Mass., who now works in the engineering and planning department for a company that designs animal shelters, said the research and teamwork were the big pluses for her.

“I worked on most of the industrial timing and planning,” Sanita said. “We had to show that we would be able to cut the time needed to perform traditional inspections. We had to be self-motivated to get our individual pieces of the project done.”

She said it was cool to be on airport runways, but that the work was demanding. “There were definitely times when we wanted to take a break, but when my teammates said they needed something, I got to work because I didn’t want to hold them up.”

Barrington’s Julian Andriulli said he focused on systems engineering with the “Eagle Eye” project.

“For me, this was very useful because I was able to focus on organizational problem-solving,” Andriulli said. “I like dealing with organizational structure and microscopic and macroscopic properties. I don’t think you get this with a typical mechanical engineering project.”

Andriulli said he found it was difficult at first for the team to come together.

“We are very different people, with different skills and mindsets and getting everyone to work together was tough at first,” Andriulli said. “But those differences helped us create a well rounded project. If you can’t work collectively or efficiently as a group, no matter how great each individual is, you are not going to make a great product.”

Westerly resident Scott Liguori, a team member who now works at Electric Boat, in Groton, Conn., said one of the challenges of the project was paring down all of the ideas to a manageable project that would result in an outcome and/or product.

“The goal of our project was to cut down on the number of inspectors needed and to speed up the process so airports will be able to open runways more quickly to more aircraft,” Liguori said. “At the Newport airport, there is a swampy area that inspectors can’t observe. With the drone, we were better able to inspect the fences in that area.”

Like his teammates, he learned a great deal from his team, Nassersharif and Warcup.

“I learned a lot from working with James Warcup about airports, their security and the problem-solving and engineering problems in general. These are things I can apply at work.”