KINGSTON, R.I. — March 2, 2018 — What were the precursors to the European financial crisis and subsequent weakening of the European Union? What are the contributions of business to economics, and what are economists and other theorists saying about Marxian economics today?

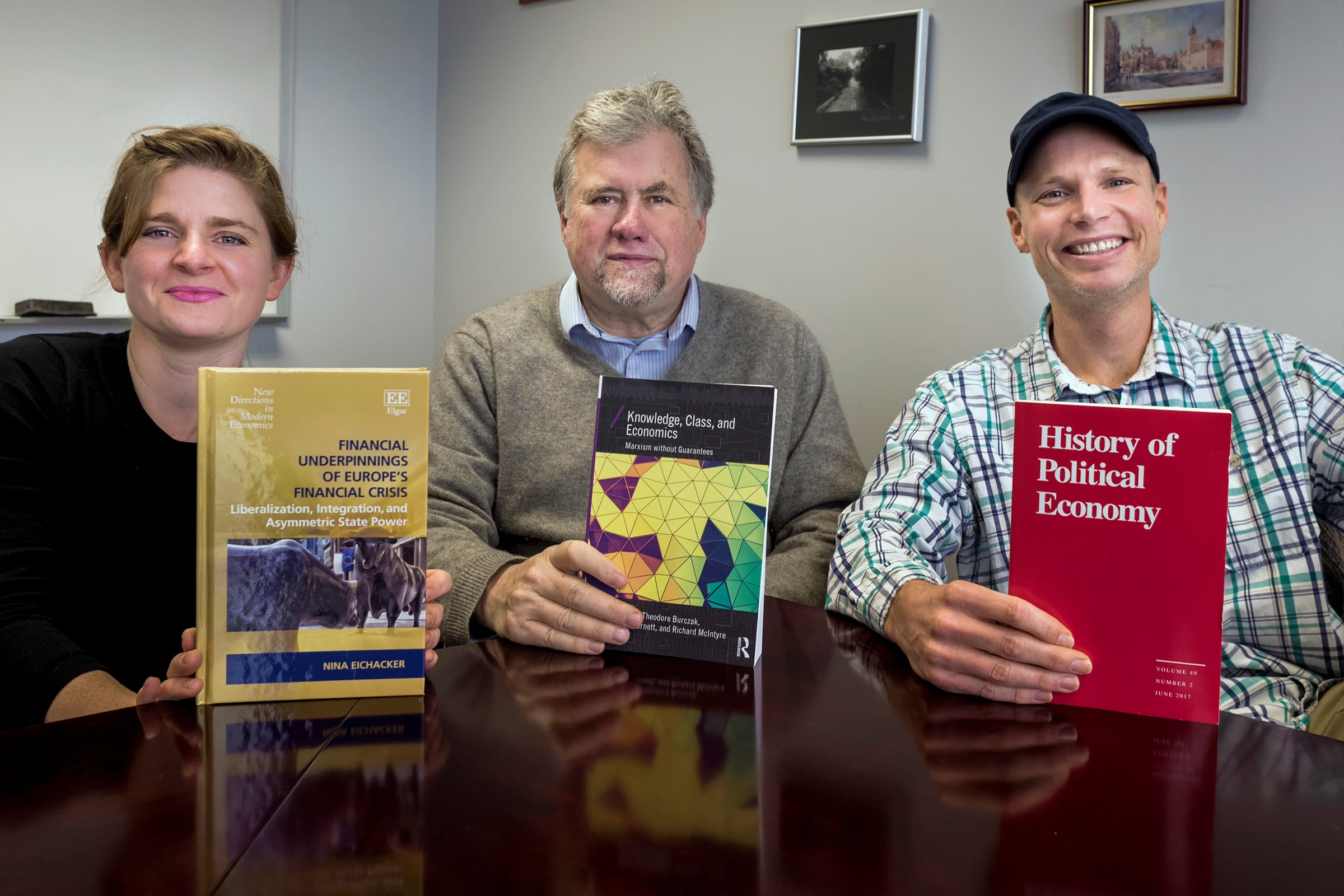

Three University of Rhode Island economists provide answers in three books published last fall:

- “Financial Underpinnings of Europe’s Financial Crisis–Liberalization, Integration, and Asymmetric State Power,” by Nina Eichacker, assistant professor of economics and resident of Hull, Mass.

- “History of Political Economy–Symposium on the Contributions of Business to Economics,” co-edited by Robert Van Horn, associate professor of economics, and resident of South Kingstown.

- “Knowledge, Class and Economics–Marxism without Guarantees,” co-edited by Richard McIntyre, professor and chair of the Department of Economics, and resident of South Kingstown.

McIntyre, a URI graduate, who earned his doctorate in economics at the University of Massachusetts, where he studied with Stephen Resnick and Richard Wolff of the Amherst School, said these new publications illustrate the wide range of prospective students will get when studying economics at URI.

“We are delighted to have faculty like Nina and Rob, who cross disciplinary lines, and who look beyond traditional economics,” McIntyre said. “Through their research, they give students unique perspectives on how economics, politics, business, financial policy and banking and social issues are interconnected. Our students are learning how these factors influence each other across the globe.”

Eichacker, an economist who studies political economy issues, said her research focus is the intersection of political science and economics.

“I look at how governments implement policies and how those policies affect the economy,” Eichacker said.

In her book, Eichacker examines the precursors to the austerity measures put in place by several European countries, including Greece, Spain and Ireland. “I look at what precipitated those steps, including the government takeovers of financial institutions. I found that European integration led to destabilization of the financial system.”

She also found that certain European countries have great power, and they were the ones that required countries in crisis to implement austerity measures to qualify for bailout money.

“This went against International Monetary Fund policy,” Eichacker said. “We know now that the austerity measures caused extensive damage, and sparked public health crises, unemployment and poverty and precipitated what we see now as an erosion of the strength of the Eurozone.”

Van Horn’s book is a result of a conference he co-led at Duke University that brought together historians of economics, business historians, scientists and sociologists.

“We brought together 12 people doing original work in different disciplines,” Van Horn said. “This is a creative group of people that look outside of economics for inspiration.”

One of the perspectives found in the book is from William Deringer, assistant professor of science, technology, and society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

“One essential notion behind Trump’s run for the presidency is the notion that he has some kind of critical knowledge about economic things that will be useful for running an entire nation. What is the long history of that idea–that a businessperson or businesspersons are the people best equipped to consider national economic policy. Or look at Trump’s recent announcement of his crack economic policy advisers. No academics, basically all billionaire businesspeople.

“What makes this a valid collection of ‘economic experts’ in the eyes of Trump and his supporters? What makes it an invalid collection in the eyes of his detractors?”

The book edited by McIntyre, “Knowledge, Class, and Economics,” looks at how the Amherst school changed Marxian economics by rejecting economic determinism and focusing on Marx’s class theory. It contains essays such as “Migrant workers in Post-Reform China,” “Bad Communisms,” “The Work of Sex,” “Rethinking Labor, Class and Justice” and “Family Farms, Class and the Future of Food.”

McIntyre collaborated with colleague Michael Hillard, professor of economics at the University of Southern Maine, on the essay “Management Ideologies and the Class Structure of Capitalist Enterprises: Shareholders vs. Stakeholderism at Scott Paper Company.”

Hillard and McIntyre examined the case of the Warren Mill in Maine that was once owned by a family, but is now owned by Scott Paper.

“Marx was interested in the creation of profits through labor and the distribution of those profits to banks, merchants and corporations,” McIntyre said. “What is relatively new is the notion that the most important thing for a business to do is to maximize profits for stockholders.”

In the case of the paper mill, there was at one time a patriarchal-class relationship, McIntyre said.

“While the workers were critical to building surplus value, the owners would turn some of that surplus back to the community through the family’s philanthropic efforts to enhance the public good. Thus came the notion of the mother mill. Workers were exploited, but at least the money stayed in the local economy.

“I don’t want to romanticize the patriarchal system, but when the Warren Mill was bought, there was a shift from a focus on the community and enterprise to financial results.”