Papers discovered by URI staff show chief justice was anti-Irish

Papers discovered by URI staff show chief justice was anti-Irish

KINGSTON, R.I. – June 3, 2008 – A University of Rhode Island staff member and professor have discovered papers belonging to Job Durfee, the 19th century Supreme Court chief justice who presided over the last case involving capital punishment in Rhode Island.

Scott Molloy, professor of labor and industrial relations at URI’s Schmidt Labor Research Center, called it the most important find of his professional career.

The papers were discovered by Christine King, a data control clerk at the Office of International Education, who grew up in a Revolutionary War era home in Tiverton. She contacted Molloy about several hundred pages of mid-19th century papers she saved from the scrap heap more than three decades ago. King grew up in the house with four generations of her family, and when she moved, she took some old hand-written notes that she had found in the attic that were being left behind as scrap.

After poking through the papers over the years, King realized the manuscripts were those of Chief Justice Durfee, who headed the Supreme Court from 1835 until his death in 1847. He grew up in the same house as King.

Molloy, an expert on labor, Rhode Island and Irish-American history, immediately realized that Durfee was a key participant in three of the state’s most volatile and contentious trials ever: the murder of a female factory worker by a local Methodist minister in 1833; treason charges against Thomas Wilson Dorr, who led a statewide rebellion for voting rights for immigrants and the poor in 1842; and a murder conspiracy case against an immigrant Irish family named Gordon for the alleged brutal killing of a prominent Cranston industrialist, Amasa Sprague in 1843. U.S. Sen. William Sprague and his brother, Amasa, ran the A&W Print Works, still in business today as Cranston Print Works.

Molloy, an expert on labor, Rhode Island and Irish-American history, immediately realized that Durfee was a key participant in three of the state’s most volatile and contentious trials ever: the murder of a female factory worker by a local Methodist minister in 1833; treason charges against Thomas Wilson Dorr, who led a statewide rebellion for voting rights for immigrants and the poor in 1842; and a murder conspiracy case against an immigrant Irish family named Gordon for the alleged brutal killing of a prominent Cranston industrialist, Amasa Sprague in 1843. U.S. Sen. William Sprague and his brother, Amasa, ran the A&W Print Works, still in business today as Cranston Print Works.

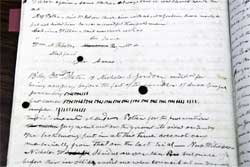

About 150 of the 350 pages of the material constitute the judge’s notes during many Supreme Court hearings in the 1830s and 1840s, records not included in the Rhode Island Historical Society’s collection. King and Molloy are turning over the collection to the society.

Amasa Sprague was found bludgeoned to death on New Year’s Eve, 1843. Six months earlier he had used his political influence to convince the Cranston City Council to lift the liquor license of Nicholas Gordon, an Irish immigrant who ran a small store and pub near the Sprague calico factory where workers drank during their lunch breaks.

Molloy said blame for the apparent revenge killing immediately fell upon Nicholas Gordon and his family, leading to three separate trials in 1844 through 1845.

Molloy, who assigns a book about the Gordon murder trial during his Rhode Island history course, was overwhelmed by the six long pages of notes for the second Nicholas Gordon trial. “Judge Durfee provided instructions to the jury about how to interpret testimony and conversations during the deliberations,” Molloy said. “During the first trial, the chief justice told the jurors to give greater weight to Yankee witnesses than Irish ones.”

Nicholas’ two younger brothers, John and William, faced the jury first in 1844 for conspiracy to murder Sprague. The jury found William innocent and John guilty based on contradictory circumstantial evidence. John was scheduled to be hanged in February 1845. In the interim, Nicholas Gordon faced the same charges in 1844, but the jury could not reach a unanimous decision. Nicholas Gordon was scheduled to be re-tried in April 1845, two months after John was going to be hanged. Both the governor and the General Assembly refused to postpone John’s execution until after Nicholas’ second trial to see if there was a conviction and a true conspiracy. Meanwhile, John died on the prison gallows where the Providence Place Mall now stands. The Yankee jury never scheduled a third trial and so a conspiracy was never proven. Nicholas Gordon died of natural causes 18 months later.

“Just seeing the names of so many identifiable witnesses that loom so large in the events made me feel like a real witness to history, especially knowing that the accounts come from Job Durfee’s own hand,” Molloy said.

“The proceedings were riddled with prejudice against newly arrived Irish Catholics,” Molloy said. “Durfee upheld almost all objections raised by the prosecution while overruling most defense challenges. At the time, the state Supreme Court also served as its own appeals court, flatly refusing to recognize any bias on its part.

“Ironically in 1852, just five year’s after Durfee’s death, the state outlawed the death penalty. John Gordon was the last person executed by the state of Rhode Island.”

Pictured above

Scott Molloy

RECORD OF HISTORIC TRIAL: These papers show notes made by Job Durfee, the 19th century Rhode Island Supreme Court Justice, in the murder- conspiracy case against William, John and Nicholas Gordon. Seen here are Durfee’s notes on the Nicholas Gordon case. URI Department of Communications & Marketing photo by Michael Salerno Photography.