KINGSTON, R.I. – May 6, 2014 – It’s no secret that many children in Rhode Island struggle to gain basic reading skills. A unique literacy program offered by the University of Rhode Island hopes to get kids turning the page, and in a studious setting – the library.

KINGSTON, R.I. – May 6, 2014 – It’s no secret that many children in Rhode Island struggle to gain basic reading skills. A unique literacy program offered by the University of Rhode Island hopes to get kids turning the page, and in a studious setting – the library.

URI’s After School Literacy Program provides one-on-one literacy testing and instruction to children in kindergarten through high school who are challenged by reading. URI graduate students – working teachers studying to become reading specialists – teach the children.

One of the unusual aspects of the program is that it is held at URI’s Robert L. Carothers Library and Learning Commons on the Kingston campus. Students use smart boards and other technology to tackle comprehension, fluency and vocabulary.

Mastering the written word is important. Studies show that kids who struggle with reading often fall behind in other subjects, too, which can lead to frustration and anxiety outside the classroom as well.

We sat down with Theresa Deeney, an associate professor in the Department of Education and director of the program, to talk about how to teach children with reading challenges, how parents can sign up and, of course, what it’s like for youngsters to go to college.

We sat down with Theresa Deeney, an associate professor in the Department of Education and director of the program, to talk about how to teach children with reading challenges, how parents can sign up and, of course, what it’s like for youngsters to go to college.

Tell us about URI’s After School Literacy Program?

The After School Literacy program helps several groups. It is a community outreach program for Rhode Island students who struggle with grade level reading and writing; the clinical practicum for URI graduate students enrolled in the master of the arts in education/reading specialization program; and a service opportunity for URI education undergraduates. Thirty percent of Rhode Island’s fourth graders lack basic reading skills, according to the National Assessment of Education Progress. Since 2002, the URI program has helped more than 90 students with language and learning disabilities, including dyslexia. Formerly held in Chariho, Providence and South Kingstown schools, the program moved to URI’s Curriculum Materials Library in 2009 so teachers could take advantage of its state-of-the-art technology and resources.

You mentioned that a grant from The Champlin Foundations has helped keep the program going? How so?

In 2010, URI received a Champlin grant to create a technology network for students with disabilities to help all students gain equal access to education. URI students with disabilities use the network for their classes, but we also use it to teach our education students how to use technology to help youngsters learn. In the case of reading, we have tools that convert speech to print, print to speech and help students with comprehension, fluency, vocabulary and basic skills. We were also fortunate to receive money through another grant to obtain laptops, desktops, smart boards and iPads. These not only help our students who struggle, but ensure that our URI education students keep up with changes in education in the 21st century.

In 2010, URI received a Champlin grant to create a technology network for students with disabilities to help all students gain equal access to education. URI students with disabilities use the network for their classes, but we also use it to teach our education students how to use technology to help youngsters learn. In the case of reading, we have tools that convert speech to print, print to speech and help students with comprehension, fluency, vocabulary and basic skills. We were also fortunate to receive money through another grant to obtain laptops, desktops, smart boards and iPads. These not only help our students who struggle, but ensure that our URI education students keep up with changes in education in the 21st century.

Why is it so important for children to learn how to read at an early age?

Reading is the foundation for much of the learning that goes on in school. We strive to get all students reading at expected levels by third grade. It’s often said that third and fourth grades mark the transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn,” and that is true in many ways. After third grade, children need to use reading to learn new information. We know from research that students who have not developed grade-level reading skills by third grade struggle in reading and other subjects, too. Not only do they struggle to catch up, they also get further behind. The more-able readers are reading a lot and exposed to more information, more vocabulary and higher concepts, while the students who struggle read less, are not encountering sophisticated vocabulary and are having difficulty picking up content from reading. We call this the “Matthew Effect,” or the “rich get richer” phenomenon in reading.

Who participates in the program?

We work with Rhode Island children in kindergarten through high school who have significant difficulty in reading. Our students are not on grade level – in fact many are several years behind grade level in reading. Some of our students struggle with basic reading skills like phonics and word reading, others struggle with comprehension, while others seem to struggle with all processes related to reading.

How do students get to the library for classes?

Students’ parents bring their children and pick them up every week. This can be challenging for someone without means, so we’ve crafted creative ways to help families in need. We’ve arranged carpools and have worked with one school to have someone provide transportation. The program has brought students and families from Richmond, Charlestown, South Kingstown, North Kingstown, Exeter and Portsmouth to “college,” and has served to inspire students who may not have the means, or who have not felt higher education was within their grasp.

How do you decide what instruction to provide?

Our job in the program is to use assessments to determine a student’s strengths and needs, and then to develop an individual instruction plan. We do coordinate with schools. With parent permission we gain the student’s school records and evaluations and talk with the student’s teachers. We use the school and our own information to better understand what’s going on with the student.

What strategies are used to teach reading to children with dyslexia?

Students struggle with reading in different ways for different reasons. Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability. Students with dyslexia have trouble with word recognition and phonics – in other words, with getting words off the page. Because of challenges with these basic reading skills, they usually also have difficulty with spelling and writing and with reading fluently. Many students with dyslexia are helped by very structured, systematic language-based instruction provided in a way that involves their bodies as well as their eyes and ears. We call this “multisensory” instruction. We also have to keep in mind that reading is incredibly frustrating for children with dyslexia. This frustration can present itself in lots of ways – not wanting to read, having trouble maintaining attention, feelings of failure. Many students may have trouble understanding why they are not able to do something that seems to come so easily to others. It’s so important to really capitalize on students’ strengths and to help them feel successful.

Are parents happy with the program?

Parents of students who struggle are desperate to find their children help to be successful, so, as you can imagine, our parents are very grateful. Some of our parents may have struggled with reading in school themselves. I hear a lot of stories about that. Those who have not attended college may find it a little intimidating to come to a college campus. Once here, they realize it’s not so threatening. URI is, after all, a public university, and all are welcome to use the resources in the library. Some of our parents stay during the tutoring sessions and use the computers, read the newspapers or grab a snack from the Daily Grind kiosk nearby.

How can parents sign up?

Our program runs alternate years, so the next program will be in the fall of 2015. Parents can call or email me for an application. My phone number in the Department of Education in the College of Human Science and Services is 401-874-2682. My email is tdeeney@uri.edu. We also post flyers in schools and in the community.

One last question: It must be fun for students to take classes at the library. Do you see a lot of smiles?

Since the program is after school, and our teachers all teach school, we can’t start until 4. Our children leave at 5:30. Parents are always worried about having trouble getting their children to come – they’ll be tired; it’s a long day. I assure them the opposite will be true, and usually it is. We have trouble getting the students out the door, not in: “Let’s go, Mom (or Dad) is waiting!”

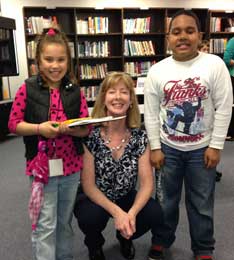

Pictured above

Theresa Deeney, of Wakefield, associate professor in the Department of Education and director of the University of Rhode Island’s After School Literacy Program, celebrates a successful year with two students, Shawnee Spears, 8, and Xaviest Rosario, 9, both of South Kingstown.

Jonathan Kelly, of Wakefield, a graduate student in the Department of Education, and Dawson Dickinson, 10, of South Kingstown, use a smart board to create a digital story.

Natalie Mallilo, of Warwick, a graduate student in the Department of Education, uses letter cards with Nathan Boyd, 7, of Richmond, to form words.

Photos courtesy of Theresa Deeney